Cost of 2019 election.

2019 Presidential elections: What data tells us could happen

By Sodiq Ajala, Mayowa Adeniran, Fumilayo Ishola, Alexander Onukwue

When Professor Attahiru Jega announced the official results of the 2015 presidential election, a majority of Nigerians jubilated. Not convinced, many skeptics imagined what could happen should the incumbent government refuse to accept the outcome. A national uproar was possible but, thankfully, did not materialize. President Goodluck Jonathan graciously conceded, passed the baton to Muhammadu Buhari, and made way in the Villa for a new government to march on.

Another presidential election is here. Nigerians are about to decide who will rule them for the next four years or beyond, a decision enabled with the aid of the permanent voters’ card – PVC. Voter registration figures for the coming polls suggest Nigerians want to have a say. INEC says this year’s voter register includes an unprecedented 84,040,084 names, representing a 20% increase from the last election cycle.

Narrowing down on voters’ registration geo-politically

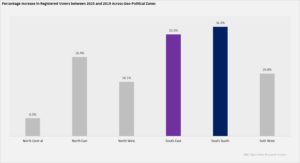

A close look at voter registration by geopolitical zones over the years opens up an interesting discussion. The North West had the highest number in 2011 and 2015. But while they retain the distinction in the current election cycle, the highest increase in voter registration between 2015 and 2019 occurred in the South-South and South East geo-political zones. What does this hold for the election?

Statewise, Delta and Rivers recorded the highest increase in new voters across the country. In Delta, a keen contest leading up to the governorship elections may have precipitated the surge in new registrations. The APC gubernatorial primaries involved, among other heavyweights in the state, Prof Pat Utomi. Also, the state’s former Governor, Emmanuel Uduaghan, is a candidate for a senatorial seat under the APC, with his successor Ifeanyi Okowa seeking re-election. A similar scenario is at play in Rivers state where the incumbent PDP Governor Nyesom Wike is aiming to neuter any influence by former governor Rotimi Amaechi. The Transport Minister is tasked by the Buhari re-election campaign to do more to capture more votes in the state this time than in 2015.

At the other end of the scale, the North Central zone has the lowest increase in voters registration while the North East ranks third. The two zones house Plateau, Benue, Borno, the most troubled states in Nigeria. Residents of these states have suffered Boko Haram insurgency and Herdsmen attack more than any other state in the northern zones. A closer look at individual zones shows that similar patterns exist in the two zones. The number of new registrants in the troubled states are close. The three states have about five hundred thousand increase.

What else could trigger the residents of these states to come out en masse and register if not to vote out the current administration? A stream of protest votes is on the cards.

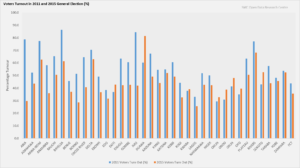

A Twist: Only half of those who register actually Vote

Nigerian democracy is growing but there is a wired pattern. If voters registration is equal to voters turn out, more than 84 million Nigerians should be out on the streets on February 16, at different polling units to exercise their voting rights. But from what past elections teach us about voter turnout in Nigeria, what should we really expect on Saturday?

In fact, only about five out of 10 of the people who claim they want better governance, having gone through the exercise of getting registered, actually turn up on D-day.

INEC is empowered by law the conduct elections. It is estimated to have more than $500 million (precisely N189,207,544,893 was approved by the Senate in 2018) at its disposal to run this year’s polls in as fair a manner as possible. Organizing and carrying out elections in a country such as Nigeria – which is currently dealing with major economic and security issues – can lead to a number of problems before, throughout and after Election Day. These problems can keep people away from polling station.

In 2011, 73,528,040 Nigerians registered but 39,469,520 votes (53.6%) were cast on Election Day. Four years later, participation fell by nearly 10% as less than half of the 66,924,005 registered voters turned out.

The number of registered voters suggests many Nigerians are interested in the democratic process. What then causes political apathy or indifference on election day?

Violence and Insecurity: Every election comes with the risk of violence. Knowing the history of violence during elections in Nigeria, this can constrain enthusiastic turnout, and even call into question the credibility of an electoral process. Casting their vote is the sovereign right of every citizen in any democratic government and one must be able to do this with ease and safety, free from undue interference and free from fear of any kind. Security is a major concern and its importance during elections is therefore obvious; it would make sure numerous stakeholders are able to discharge their responsibilities under the Constitution and the Electoral Act.

President Buhari is vying for a second term but nominations for other positions within the ruling All Progressive Congress, APC, have been highly contested. This led to fragmentation within the party, defections to other parties, and some violence – as seen recently at an APC Rally where the treasurer of the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW), Musiliu Akinsanya a.k.a MC Oluomo, was stabbed. NURTW is tasked with the duty of logistics during the elections, in conjunction with the Federal Road Safety Commission (FRSC)

Cases of violence took place in the aftermath of the 2011 elections. Election Day violence was also serious in the 2007 elections, with an estimated 40-50 deaths related to electoral activity and numbers of reports of ballot box thefts, burning of local INEC offices and mobs storming offices to steal ballots and other materials. The political offices of one Delta State candidate for the House of Representatives were bombed.

There are growing concerns that the 2019 elections will be marred by violence, in Rivers State, for example, between supporters of incumbent Governor Nyesom Wike of the PDP and his APC competitor, Rotimi Amaechi, the minister of transportation – who backs Arch Tonye Cole for the gubernatorial seat.

Public confidence in INEC is mixed. Although applauded for organizing broadly credible elections in 2015, can the progress be sustained in 2019? For many Nigerians, electoral violence results from processes that are further compromised by the actions or inactions of the INEC or the security agencies. There are some reports that the security forces have served political ends and that many candidates gather gangs of “area boys” around them with both defensive and aggressive purpose.

Electorates’ Perception Of The Election: The “my vote doesn’t count idea”

Low voter turnout can also indicate that Nigerians are growing increasingly disillusioned with the young democracy and have little faith that their votes count. This is widely read across the social space where youth who make up a huge number of eligible voters, believe that the election results have already been decided even before people have had the opportunity to cast their votes.

The youth hardly believe in the government as they think the government only pay lip service to campaign promises. This can have a psychological effect. The general belief is that politics is only meant for some set of elites in society and others don’t have a chance.

Credibility of the Elections: Recurring incidents include underage voting, voter registration list errors, stuffed ballot boxes, group voting, party observers and the police instructing individuals on who to vote for, lack of privacy for voting and lack of results; all these make the voting process questionable.

Security agents have been seen to snatch ballot boxes in the open. Even with the revolution in technology and its use in election administration, there are still remarkable challenges faced. Counting is still being done manually. The absence of adequate security, as well as inadequate electoral transparency, could well lead to increased violence upon the conclusion of the elections.

INEC must proactively maintain and ensure that the electoral process is transparent to Nigerian voters and international observers if it is to maintain its credibility and public peace.

Voter Education And Ballot Design:Towards the 2019 elections, most voters were told where and how to register to vote but two crucial sets of information not widespread are the location of their assigned polling station and how to properly cast a vote. Thankfully, internet penetration has increased to over 90 million yet people still need information on voting stations and how to vote well.

Many groups, including Nigerian political parties, have voiced concerns about INEC’s chosen ballot design. Many voters find the ballot confusing and difficult to fill out properly, thus raising the likelihood of casting invalid votes.

Two basic problems have consistently been pointed out. First, the ballots for each election were indistinguishable except for the name of the election printed at the top. Each displayed symbols for all registered political parties even in areas where only a fraction of those parties were, in fact, fielding candidates.

Second, voters would be asked to indicate their preference by placing a thumbprint in space looks far too small for an average size thumbprint to fit. The voter would then fold the ballot in a manner that would make it very likely that the thumbprint would stain other portions of the ballot, thereby casting doubt on the voter’s true intention.

A widespread WhatsApp message from a new political party is encouraging voters to vote with their little finger instead of their thumbs to avoid being invalidated in the 2019 elections. INEC must engage in a sustained public education campaign in the lead-up to the 2019 elections, including mass media campaigns.

Logistics: With 119,973 polling stations across the country, any delay in getting the ballots to the field can significantly affect opening times at polling stations, especially in rural areas. Ballots are known to travel from several central distribution centers, then have to be hand-counted and handed to the relevant officials for each polling station. There are many incidents of ballots not distributed in a timely manner.

Haphazard ballot distribution throughout the country has in the past, led to the disenfranchisement of a significant number of Nigerians; many people couldn’t vote due to late poll openings and some polls received no ballots at all. The NURTW and FRSC are mainly responsible for the logistics of voting materials. Are they efficient enough or need increased capacity or is the disorganization deliberate? INEC needs to develop stronger logistical plans with more flexibility to prevent a recurrence of these issues.

Ballots can be stored and distributed from locations within a reasonable distance of their appropriate polling stations. This may require a significant increase in the number of centralized locations and, possibly a decrease in the number of polling stations.

Unordered Voter List: Confusing voter rolls/lists can have a dampening effect on voter turnout and willingness. Voter rolls are usually not ordered and standardized. Voter lists need to be physically displayed within the timeline mandated by the Nigerian Electoral Act. Internet listings are still not yet sufficient with our level of internet penetration. At a minimum, they must be ordered, either alphabetically or numerically.

According to reports from observers from the International Republican Institute, in 2007, presidential ballots were not serially numbered, unlike the national assembly ballots. This singular failure opened the entire electoral process to fraudulent activity as there was no way to track, or prove in court, that fraud took place without being able to individually identify ballots.

Location Disenfranchisement: The idea that electorates have to vote at their registered locations needs to be looked into. Voters’ turnout can be a determinant of the election outcome. This brings to mind the just ended 3-month industrial action by the Academic Staff Union of Universities, ASUU, which has most students (who make up a large chunk of eligible voters) out of school since November 5, 2018.

Although, the strike is called off recently (about a week to balloting day), many students would rather be in the safety of their homes until after the election with the exception of very enthusiastic voters.

Voters’ Turnout and Winning Strategy

Elections are a game of numbers. In the Nigerian system, every vote counts. The effect is that getting voters to come out on Election Day is a necessity for all parties. If voters registration number were to be used as a stepping stone to winning, two states will be key to determining the 2019 presidential election result in the SSouth-South geopolitical zone for the main opposition party. Rivers and Delta will be key states for the PDP’s hopes of winning the 2019 presidential elections. Besides being the only states to give the party up to a million votes in 2015, both have the highest number of newly registered voters this year. The increase in new voters is important. The party should use these numbers to their advantage.

Defeating the present administration requires a torrent that will neutralize the bulwark of the North Western votes. Over the past two election cycles, votes from the North West have belonged to President Buhari, forming part of his acclaimed ‘constant 12 million votes’. In 2015, three states – Kano, Katsina and Kaduna – gave the president up to one million votes each and the difference between these five states – 1,678,720 votes – made up 70.77% of the APC’s total margin of victory. Assuming the region holds firm for the president, it is imperative that the opposition’s strategists get the maximum possible turnout from the South-Southern stronghold states.

Crashing the North West

But does the PDP have a chance at cracking the North West wall this time?

Zooming into the political ambiance and the realignments of influential figures in the region show a possibility. In Kano, a battle of egos between state governor Abdullahi Ganduje and his predecessor Senator Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso led the latter to return to the PDP sometime in 2018. Kwankwaso’s huge following in the ancient city, dating back to his days as the state governor, is a formidable, indispensable asset for the Atiku Abubakar campaign if well directed. The Kwankwasiyya movement contributed to the APC’s margin of victory in Kano in 2015 being 1,688,220 votes; splitting that difference as well as claiming the majority of the over 500,000 newly registered voters is the strategy to employ.

Also, the president’s home state of Katsina has voted for the PDP in elections before, being the home state of former president Umaru Musa Yar’Adua. President Buhari won it in 2015 by 1,246,504 votes but there is a modest chance for closing the gap, beginning with laying claim to a majority of the 385,489 new voters in the state. For the PDP, the aim here will be to keep the APC’s potential margin of victory close, while getting the most of its strongholds in the South.

But where it is about keeping it tight in Kano and Katsina, there is a potential for a flip in Jigawa. Located between Kano and Yobe states (in effect the North West/North East border state), Jigawa has the highest increase in the number of voters in the country behind Rivers and Delta states. Combined with the fact that it had the highest improvement in voter turnout from 2011 to 2015, the state becomes potentially decisive for the PDP should it be able to claim the majority of the votes.

Lagosians Are Busy

Indeed, Jigawa is more decisive for both parties than Lagos, the state with the largest number of registered voters.

Home to 24 million inhabitants of just about every ethnic and religious affiliation, Africa’s fifth largest economy is the most curious subject for psephologists and casual students of Nigerian elections.

Lagos is the abode of the wealthiest and most informed individuals in Nigeria. Yet, its apathy towards electoral participation could not be more ironic given the far-reaching impact politics and policy summersaults can have on commerce and industry. Voter turnouts of 33.06 per cent (third lowest in the country) and 25.67 per cent (lowest) in 2011 and 2015 respectively suggest residents have other priorities other than voting on the election day, even if the movement is typically restricted and most businesses operate skeletally.

What’s more? The margin of victory between the two major parties almost makes campaigning in the state of little significance. Of the 21 states, the APC won in 2015, Lagos ranks 15th (or seventh from bottom) in terms of the margin of victory. Essentially, it is more profitable for the APC to increase its voter turnout in Boko Haram-ravaged states like Borno and Yobe (each posted over 400,000 in victory margins) than Lagos. Apparently, supporters of both parties in the state know enough about each others’ strengths and subconsciously become reluctant to show up for the fight.

For the PDP, a similar dynamic plays out in the Federal Capital Territory, and in states like Nasarawa, Ekiti and Taraba. Though the party won these states in 2015, it was not with margins that require them pulling out all the stops for their votes this time around.

The Demographic Influence

For the first time since the dawn of Nigeria’s fourth republic, there will be voters who did not experience the military administration. Hence, there is a place for considering the character of the individuals who make up numbers that could determine the coming polls.

In consonance with population data, INEC categorizes 22.3 million voters as being students. The other categories as high are farmers/fishers, people in “Business” and housewives. These categorizations are not enough to describe how Nigerians are probably going to cast their ballots; for example, students who are also artisans may vote differently from students who are traders. Also, the geographic location, occupation and social status of the husbands of those identified as housewives could have an influence on their votes.

However, matching the candidates’ policy positions and reactions to events could help hazard a hypothesis on the sector of the economy where the candidates are likely to get their votes. Students who have been on strike for three months may likely side with Atiku Abubakar in search for new answers, while Artisans and Farmers who have benefited from social intervention programmes such as n-power, Trader Moni and Market Moni could potentially tilt towards re-electing the president. Every other category, if taken singularly, could present toss-ups.